Warren Buffett’s Rare Big Investing Mistake

When you stray from your circle of competence, bad things can happen

Warren Buffett is the world’s most successful investor. Yet, even the best make mistakes, as any good investor knows. Analyzing Warren Buffett’s mistakes in depth can make you a better investor. In the 2020 Berkshire Hathaway annual letter, Buffett briefly tells us about a recent, big, mistake: Precision Castparts (“PCC”). Let’s dive in and see what we can learn.

Buffett bought PCC in early 2016. The company is a market leader in global manufacturing of complex metal components serving the aerospace, power and general industrial markets. I am, of course, not privy to what Warren Buffett was thinking at the time. However, having studied his investing approach for decades, I can surmise that his qualitative assessment of the company was likely along the following lines:

PCC has a durable competitive advantage allowing it to earn high returns on capital

It is in a predictable business not susceptible to rapid adverse change

It has an opportunity to grow its profits over time

It is led by an able and honest CEO who is passionate about the business

From a quantitative perspective, Buffett probably saw the following:

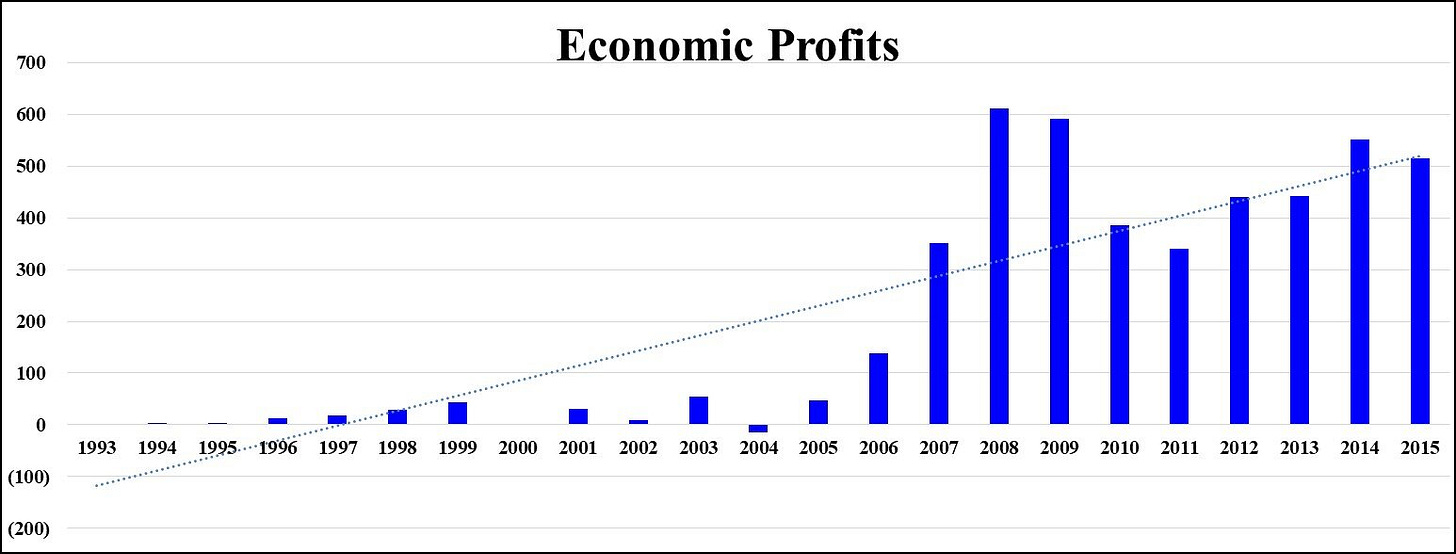

SOURCE: BLOOMBERG, MY ANALYSIS

SOURCE: BLOOMBERG, MY ANALYSIS

The first chart shows high and growing economic profit. Economic profit is defined as (Return on Invested Capital – Cost of Capital) x Capital Employed. It’s a better measure than ROIC alone, since a company can have very high ROIC on a tiny amount of capital, but that might be less valuable than a lower (but still high) ROIC on a much larger amount of capital.

The second chart shows historical pre-tax profit and free cash flow (FCF). Warren Buffett is on the record as placing a high degree of emphasis on owner’s earnings, by which he means the amount of cash that can be taken out of the business each year without reducing its future profits. Note that FCF, as calculated in the chart above to be Cash Flow from Operations less Capital Expenditures, possibly understates true owner earnings since it’s possible that a portion of the Capital Expenditures are really organic investments back into the business to generate future growth rather than to merely maintain current profits.

The total purchase price was approximately $32.7B (or $235 per PCC share), as well as an assumption of approximately $5B of PCC debt for total consideration for the enterprise of $37.7B. Warren Buffett has taught us that intrinsic value investing is always about comparing what you pay with what you get. Ideally, you would of course like to know the future owner’s earnings stream from now until infinity. Then figuring out what to pay would be pretty easy.

However nobody, not even Warren Buffett, gets to know that for sure. Each of us, including Buffett, has to form our own opinion about a reasonable range of future scenarios for the cash flow that a business can generate. The starting point is the company’s history: what has the business actually done thus far? Financial history is not enough, and we need to combine it with our qualitative assessment of the business and an informed view of how the future may differ from history in order to come up with a forecast.

So, let’s put the $32.7B equity and $37.7B enterprise consideration into context, by looking at the historical financial facts that Buffett had at his disposal when making the decision to buy PCC.

A few things should jump out at us:

The $32.7B equity price was approximately 26x prior year’s FCF, 25x the average FCF of the prior 3 years, 29x that of the prior 5 years, and 37x that of the prior 10 years

The $37.7B enterprise value translates into an Enterprise Value (EV) to Net Operating Profit After Tax (NOPAT) of 20x last year’s levels, 22x the average of the last 3 years, 25x the average of the last 5 years and 33x the average of the prior decade

These valuation metrics are far above the levels at which average companies trade at over time. Does that mean that they are necessarily too high? Absolutely not. Just because an investment is made at a high multiple of historical profits does not, in and of itself, tell us whether the price paid was too high or too low.

So what does it tell us? It tells us that for PCC to be a good investment at the price at which Buffett bought it, he needed one thing in particular to happen: future growth, and lots of it. For context, the 26x trailing FCF translates into roughly 4% cash on cash return. Buffett has been on record as saying that he does not intentionally make investments if he doesn’t think he can get at least a 10% return. The difference between the 4% that he was getting at the time of purchase, and his much loftier aspirations for return on his investment would need to come from meaningful future growth in profits and FCF.

Let’s see what happens to Buffett’s PCC investment, year by year, after Berkshire Hathaway closed the acquisition in January 2016. I have included full, detailed quotes in the appendix with links to the original source, be it annual reports or form 10-Ks and will summarize the most salient points in the article to keep it from getting too long.

In 2016, we did not get much of an update on how PCC was doing despite its size and it having been part of Berkshire for almost all of the year. In the first few years after the acquisition, disclosure of PCC’s results was sparse. After doing my best to back into the 2016 results from disclosures in future years, I can see why Buffett might not have been too excited to provide a detailed update: revenues appear to have fallen slightly and profits appear to have fallen substantially! Certainly a far cry from the growth needed to justify the purchase price.

2017 was not much better. Again, disclosures are imperfect, but I estimate that while revenue grew slightly profits (even adjusted for one-time items) declined modestly from 2016 levels. There was also an interesting comment by Buffett in the 2017 annual letter in which he states that he does not understand manufacturing operations as well as he does those of some of the other businesses that Berkshire owns. Hmmm…

2018 saw modest revenue growth. Unfortunately it did not lead to profit growth, with profits still significantly below 2015 levels. Part of the explanation was the decline in the gas turbine business, and we were told that the company is now trying to repurpose some of its assets for other uses.

2019 finally saw modest profit growth. However, by my calculations, profits were still down over a third from the 2015 levels! Recall, to justify the purchase price we needed profits that are significantly higher than 2015 levels in the future, and here we were, 4 years out, actually still down by quite a bit. The reason given this time for the challenges in the business was related to aerospace demand related to Boeing’s recall of the 737 MAX plane.

2020 needs no detailed explanation. With COVID disrupting the airline business, PCC’s pretax profits plummeted to $650M, or a small fraction of where they were in 2015. This is unlikely to be the new normal, so I don’t think it’s worth putting too much weight on 2020 levels in thinking about the business’s future profitability.

So here is what Warren Buffett was looking at after 5 years have passed since the time of the acquisition:

With the benefit of hindsight, it appears that the 2014-2015 period was an unusually good time for PCC, resulting in abnormally high profits. You could try to argue the opposite point – that each of 2017-2019 had some problem that depressed end-market demand. However, most businesses usually have some problems. That is the point of normalizing profits – it is meant to represent a typical amount of issues that a business experiences over an economic cycle.

So what were Buffett’s mistakes in buying PCC?

He didn’t properly normalize the starting profitability for an unusually problem-free environment

He invested in a business that he admitted he didn’t understand as well as some of the others that Berkshire owns

He paid a price that left little room for error – one that had little margin of safety

The last point is worth elaborating on, especially since it appears to be similar to the error that Buffett made in the Kraft Heinz deal. This is especially true since the current fashion among investors, and even among many (but not all) value investors is to sneer at the simplistic approach based on low multiples of historical profit.

Low multiples of profits in and of themselves are no guarantee of great returns. However:

Paying high multiples of past profits places a high demand on the investor’s ability to forecast the future, where coming up short of the lofty expectations priced into an investment is likely to result in permanent capital loss

Combining a low-multiple approach with a thorough qualitative analysis of the business can result in an investment approach that has high margin of safety and a more than a satisfactory return

Warren Buffett was Benjamin Graham’s best student in the latter’s Security Analysis class at Columbia. In many ways, the student has surpassed the teacher as an investor. Given that Graham is no longer with us, we of course do not know how his approach would have evolved, if at all, in the current investing environment. However, perhaps despite all of Buffett’s undisputed investing excellence, there is still something that Graham could have reminded Buffett of in 2015 as Buffett was getting ready to buy PCC:

Danger in Projecting Trends into the Future. There are several reasons why we cannot be sure that a trend of profits shown in the past will continue in the future. In the broad economic sense, there is the law of diminishing returns and of increasing competition which must finally flatten out any sharply upward curve of growth. There is also the flow and ebb of the business cycle, from which the particular danger arises that the earnings curve will look most impressive on the very eve of a serious setback.

– Benjamin Graham, Security Analysis, 6th edition, p. 364

In investing, things change very slowly. A lot slower than many who are reading this article in 2023 are likely to think they do.

As for Warren Buffett, there is one more lesson from this episode for all of us. That is how well he handles this mistake. He doesn’t hide from it. Nor does he blame extraneous circumstances, such as the COVID pandemic, or anyone else. He owns up to the mistake and learns from it:

The final component in our GAAP figure – that ugly $11 billion write-down – is almost entirely the quantification of a mistake I made in 2016. That year, Berkshire purchased Precision Castparts (“PCC”), and I paid too much for the company.

No one misled me in any way – I was simply too optimistic about PCC’s normalized profit potential. Last year, my miscalculation was laid bare by adverse developments throughout the aerospace industry, PCC’s most important source of customers.

In purchasing PCC, Berkshire bought a fine company – the best in its business. Mark Donegan, PCC’s CEO, is a passionate manager who consistently pours the same energy into the business that he did before we purchased it. We are lucky to have him running things.

I believe I was right in concluding that PCC would, over time, earn good returns on the net tangible assets deployed in its operations. I was wrong, however, in judging the average amount of future earnings and, consequently, wrong in my calculation of the proper price to pay for the business.

PCC is far from my first error of that sort. But it’s a big one.

– Warren Buffett, 2020 Annual Letter

If you liked this article, please “like” and share this article. If you are interested in learning more about the investment process at Silver Ring Value Partners, you can request an Owner’s Manual here.

About the author

Gary Mishuris, CFA is the Managing Partner and Chief Investment Officer of Silver Ring Value Partners, an investment firm that seeks to apply its intrinsic value approach to safely compound capital over the long-term. He also teaches the Value Investing Seminar at the F.W. Olin Graduate School of Business.

Note: An earlier version of this article was published here.

Excellent analysis. Thank you, Gary!

Gary, you are doing a fabulous job presenting this case. Thank you for sharing!