The Existential Challenges Facing The Value Investor Tribe

The value investor tribe could be on the path to extinction...

The tribe of value investors is small and dwindling. Some think it is or it should be on its way towards extinction. Others are seeking to redefine its identity.

It has an unofficial chieftain, Warren Buffett, its most famous and successful member. I have lost count of how many times someone has blindly quoted him in an argument, or implied that an investing action is correct because it is similar to ones taken by him.

Members of the value investor tribe are facing a difficult choice. On the one hand, a core tenet of value investing is discipline and sticking to a well-defined process. On the other hand, the last decade or so hasn’t showered value investors with much success. Certainly not compared to decades prior when successful practitioners had handily beaten the markets.

Let me paint a picture of how bad things are.

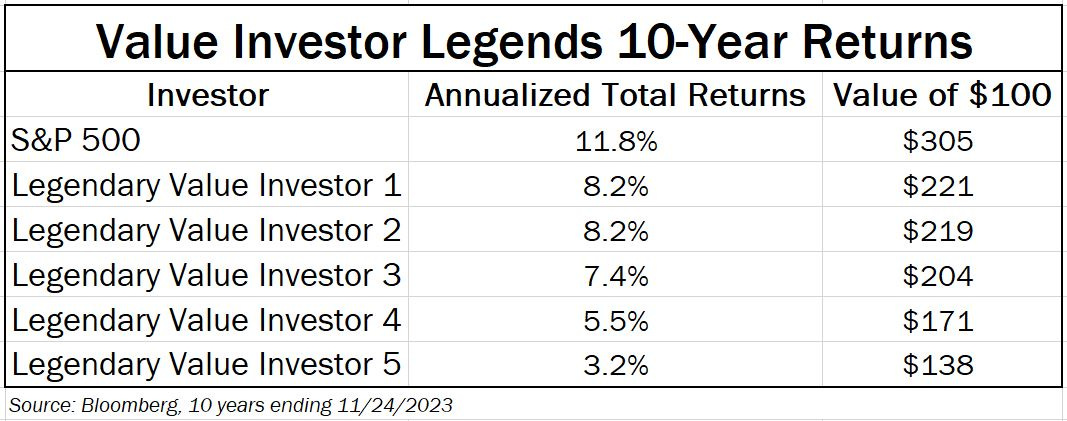

The table below presents the results of 5 value investing legends over the last decade. These are people managing billions of dollars. Some have written books. Others have made frequent TV appearances. You would know all their names if you were a member of the value investor tribe.

What’s more, at the beginning of this decade these people had something that most other tribe members did not have: a clearly-articulated value investing process with 10+ years of successfully implementing it to beat the stock market at scale.

And yet, as you can see from the table above, not one of them has come close to beating or even matching the market.

You might think that I cherry-picked these investors to make a point. I did not. I am sure there are some value investors who did fine during the last decade but let me assure you that to the best of my knowledge the list above is fairly representative of value investor experience managing meaningful pools of capital.

You might also think that maybe they all had a lot of overlap in their holdings, and it just happened that their group of stocks did poorly. Nope. These investors had different portfolios, had very different degrees of portfolio concentration and varied in the size of companies that they focused on.

So what’s going on?

The tempting explanation for someone looking to defend the tribe is that the last decade has been defined by a small group of large companies generating a disproportionately high percentage of the market’s returns. That’s true. However, if instead of using the S&P 500 index we were to use the S&P Midcap 400 index, it would still beat all of the value investor legends on the list. The S&P 500 Equal Weighted index would trounce the legends by an even greater margin, not that far off from the results of the S&P 500.

So no, we can’t lay most of the blame on the Magnificent Seven, Amazing Five, Terrific Nine or whatever moniker de-jour market watchers come up for the hot stock group of the moment.

Another theory is that a lack of a real recession in the last decade has deprived value investors of their time to shine. Value investors’ focus on protecting against things going wrong typically allows them to do better during a recession and the accompanying market downturn. Furthermore, the fear that accompanies this part of the cycle allows us to plant seeds for the future by buying bargains not readily available during other times.

We had a blip of a recession during the COVID pandemic in 2020, which was quickly snuffed out by massive amounts of government intervention. That in turn inflated a market bubble in both stocks and bonds, driving risk appetites through the roof. As a result, we are ending the period in an environment where investment attributes valued by value investors are being underappreciated by the market, while the stocks of companies most in favor now are ones that don’t fit the process of most value investors.

There is merit to this theory that a combination of not having a real downcycle in the sample combined with end-point bias of ending on a particularly challenging market environment for the value investing approach is creating a 10-year period that is not representative of most future decades in the market. However, it’s hard to know how much of the underperformance is due to this versus more permanent causes.

What are some more troubling possibilities, at least if you are a member of the value investor tribe?

One theory is that the increasing dominance of passive investing is exacerbating stock market momentum and hurting value investors. Since most indices are market capitalization-weighted, once a stock goes up some, there is now a much greater pool of capital that is forced to buy it as new money is added to the funds than there was 10 or 20 years ago. This creates a reflexive spiral where the stock market winners keep going up because… they had gone up.

I think there is truth to this theory, but it’s hard to know how much of an impact it has had. Besides, I am not ready to believe that the most efficient capital market in the world has become massively inefficient to the degree that there is a large and permanent disconnect between market prices and business values.

What other causes could there be for the challenges facing value investors?

Some years ago, Warren Buffett pointed out that the pace of business disruption has increased. That has two implications:

The past is less predictive of the future for the typical company

The successful disruptors can win faster and bigger than they had been able to in the past

Let’s examine each implication. The classic, Benjamin Graham-style circa 1940s, investing approach relies on finding companies whose securities would produce a high rate of return if their companies’ future financial performance even approximately resembles that of the past. Analysis is performed to make sure that there are qualitative reasons for the stability of past financial results, and the future is looked at as a threat rather than an opportunity for extra profit.

Graham always stressed that cheapness of the security alone, or even cheapness compared with long-term historical profitability are not enough. However, Buffett’s insight suggests a much higher rate of false positives for an investor applying the classical value investing approach. What would that look like?

You encounter a stock that is trading at a low multiple of the average profits over the past economic cycle. Not seeing any specific threat on the horizon, you, as a card-carrying member of the value investor tribe, purchase this stock. You believe the margin of safety lies in the fact that even if the future profitability is somewhat below the historical average, your returns will still be satisfactory given your low purchase price.

So, what’s the problem?

If businesses can be disrupted much faster than before, then a much higher percentage of situations of the type described above can turn out to be bad investments. Their history no longer acts as a prologue to the future, and their future profitability may be drastically below that of the past. The low price relative to historical profits alone is insufficient to prevent permanent capital loss that value investors work so hard to avoid.

Conversely, if disruptors are likely to be more often successful than they had been in the past, and perhaps successful to a much greater extent, then the conclusion might be that you want to search for investment ideas among potentially successful disruptors rather than among cheap securities. Disruptors, by their very nature, rarely have a long history of financial success. When they do, their securities rarely trade at a low price relative to those historical profits given market expectations, perhaps justified, for much better financial performance in the future.

This approach is not in itself new. It has been successfully practiced by Philip Fisher in the 1940s and the 1950s, the same time period during which Graham successfully practiced his approach. The process for implementing it has also been known for a long time, laid out masterfully by Fisher in his Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits.

What is different is that the odds of success appear to have shifted from companies defending historical competitive advantages and profit streams to those attacking them with new business models.

So the doomsday scenario for the value investor tribe can be summarized as follows:

The process that they had been following no longer works sufficiently well given the lower probability of success and the higher likelihood of large permanent losses among cheap securities

Success in picking disruptors is outside of their circle of competence

A lower batting average, higher frequency of large losses and an inability to meaningfully participate in large winners combine to deprive traditional value investing of any hope of beating the market

However, all is not lost.

Proponents of the above theory reach the conclusion that analytical efforts should be spent on finding successful disruptors. That’s not the only possible logical conclusion. If value investors can adapt by using better qualitative analysis techniques to find the smaller set of companies that have both defensible business models and cheap securities, that provides another path to success.

Let’s not forget – the Philip Fisher style of investing is going to lead to many false positives and large losses as well. The winners are not normally distributed, but rather follow the same kind of power-law probability distribution seen in Venture Capital and movies. And what do we know about the distribution of returns in Venture Capital? There is a huge dispersion of returns between the best investors and the rest, and the median return isn’t all that great.

In plain English – for every self-styled successful “compounder bro” publicly pounding their chest about their amazing business analysis skills and doing a victory lap, there might be many using a similar process with similar skill but with far inferior results. Except that they don’t advertise their lack of success, so the selection bias makes you think that the overall approach is far more likely to lead to investing success than it really is. It also might lead you to falsely believe that the person doing the public victory lap can replicate their success for many years to come.

The value investor tribe has a choice to make. The way I see it, it is to:

Abandon value investing and join another tribe

Leave the arena admitting that they can no longer add value in a changed market

Evolve their approach while retaining its core principles

I clearly favor the third choice. My conclusion, informed by the greater pace of business disruption, is that successful value investors should adapt by:

Practicing far deeper business quality analysis to select the subset of companies whose historical economics truly are defensible from disruption

Paying a far greater amount of attention to the quality of management, as in a faster-paced business world their ability to adjust to changing circumstances will play a greater role than it had in a more stable environment

Concentrating their portfolios more than they had been doing, since the combination of a defensible business, honest and competent management, and a price with low expectations has become rarer than it had been in decades past

Being willing to sit on the sidelines and wait when the desired combination of attributes is unavailable rather than compromising on either quality or price

Incidentally, that’s what it looks like the Tribal Chief, Warren Buffett is doing. Not that it makes it right or wrong. However, it’s certainly interesting to note that the man who was early in recognizing this paradigm shift of greater business disruption has had his cash hoard growing in recent years.

People all too often quote the well-worn quote of Buffett’s that “it’s better to buy a wonderful business at a fair price than a fair business at a wonderful price.” The only problem is that that’s not what the great investor actually does. He might say it to make the people selling their businesses to him feel better, but in reality he isn’t looking to pay a fair price for anything. He is looking for one thing only: to pay a price for a predictable business highly likely to result in attractive returns.

Don’t you think he knows plenty of large, wonderful businesses? You don’t think that he believes that Visa or Microsoft or pick any one of a number of successful blue chips that are widely owned these days are excellent businesses with good management? Of course he does. Why does he not own them? He doesn’t think their price offers him an attractive enough rate of return relative to that of likely future opportunities. That’s the only explanation for his growing cash hoard consistent with the facts.

We humans like simple answers. Good vs. bad. Hero vs. villain. The problems are all temporary and thus no change is required or all structural and we are doomed.

The truth about the threats facing the value investor tribe is more complicated than that. Some factors depressing results are clearly temporary – we haven’t had a real recession and downturn in a while, and the current endpoint strongly favors other approaches. However, other threats are real and require us to adapt to be successful. Not everyone is going to adapt, and of those who do, not everyone will choose to do it in the same way. However, ignoring the changed environment is not likely to be a successful option, for the environment is certainly more difficult to navigate than in prior decades, and thus requires not blind adherence to old rules, but thoughtful implementation of classic ideas in new ways.

If you liked this article, please “like” and share this article. If you are interested in learning more about the investment process at Silver Ring Value Partners, you can request an Owner’s Manual here.

About the author

Gary Mishuris, CFA is the Managing Partner and Chief Investment Officer of Silver Ring Value Partners, an investment firm that seeks to apply its intrinsic value approach to safely compound capital over the long-term. He also teaches the Value Investing Seminar at the F.W. Olin Graduate School of Business.

Well thought out with many excellent points. Deeper dives seems to me the most probable method of success, with longer tracking periods of familiarity on possible candidates.

Thanks for sharing your perspective.

Becoming more mindful about one's own investing behaviour and decision-making is another way how to improve one's investment returns and set yourself apart from the rest. Something, I feel, is often overlooked by most investors.