Lessons From Warren Buffett’s See’s Candies Acquisition

“Let’s take a look at what kind of businesses turn us on"

“Let’s take a look at what kind of businesses turn us on. And while we’re at it, let’s also discuss what we wish to avoid.” In his 2007 Berkshire Hathaway annual letter, Warren Buffett provides us with a primer on what to look for in businesses, and on what to avoid. He also does something rare – he gives us a detailed post-mortem analysis of his 1972 purchase of See’s Candies. Both have a lot of gems of wisdom for us to enjoy and learn from.

Charlie and I look for companies that have a) a business we understand; b) favorable long-term economics; c) able and trustworthy management; and d) a sensible price tag.

This combination is clearly desirable, but rare

Insisting on a limited sub-universe of businesses, attractive company economics, good management and a good price naturally leads to a fairly concentrated portfolio

Buffett says “sensible price,” but he doesn’t really mean that, as we will see later. He means a really low price relative to his estimate of the intrinsic value of the business. He just doesn’t want to offend past and future business owner sellers to Berkshire by stating that outright

A truly great business must have an enduring “moat” that protects excellent returns on invested capital. The dynamics of capitalism guarantee that competitors will repeatedly assault any business “castle” that is earning high returns. Therefore a formidable barrier such as a company’s being the low-cost producer (GEICO, Costco) or possessing a powerful world-wide brand (Coca-Cola, Gillette, American Express) is essential for sustained success. Business history is filled with “Roman Candles,” companies whose moats proved illusory and were soon crossed.

Our criterion of “enduring” causes us to rule out companies in industries prone to rapid and continuous change. Though capitalism’s “creative destruction” is highly beneficial for society, it precludes investment certainty. A moat that must be continuously rebuilt will eventually be no moat at all.

Attractive economics are only good if they are enduring, and that requires the company to be able to sustainably do something that others can’t replicate

There are a few patterns that give rise to a sustainable competitive advantage, such as structurally lowest-cost, permanent differentiation and economies of networks

Most companies don’t possess any of these

Investing involves estimating the future, and businesses prone to rapid change make that too hard

Additionally, this criterion eliminates the business whose success depends on having a great manager. Of course, a terrific CEO is a huge asset for any enterprise, and at Berkshire we have an abundance of these managers. Their abilities have created billions of dollars of value that would never have materialized if typical CEOs had been running their businesses.

But if a business requires a superstar to produce great results, the business itself cannot be deemed great. A medical partnership led by your area’s premier brain surgeon may enjoy outsized and growing earnings, but that tells little about its future. The partnership’s moat will go when the surgeon goes. You can count, though, on the moat of the Mayo Clinic to endure, even though you can’t name its CEO.

A single great individual is a fragile source of advantage and can disappear unexpectedly

However, if that leader translates their greatness into enduring business characteristics, then the competitive advantage can become permanent (e.g. Steve Jobs and Apple)

Long-term competitive advantage in a stable industry is what we seek in a business. If that comes with rapid organic growth, great. But even without organic growth, such a business is rewarding. We will simply take the lush earnings of the business and use them to buy similar businesses elsewhere. There’s no rule that you have to invest money where you’ve earned it. Indeed, it’s often a mistake to do so: Truly great businesses, earning huge returns on tangible assets, can’t for any extended period reinvest a large portion of their earnings internally at high rates of return.

Investors focus too much on growth and not enough on predictability of future economics of a business

As we shall see, they also underestimate the value of moderate, but very durable growth

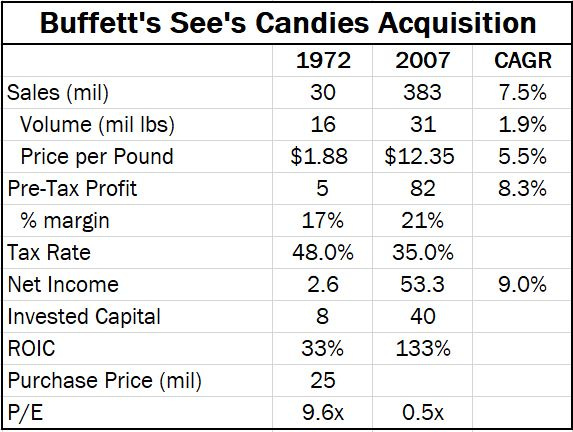

Warren Buffett rarely does detailed post-mortems on his acquisitions. He doesn’t need to, at least not in public. So it’s quite a treat to have him provide the details on one of his more iconic purchases, See’s Candies. All the more so since it marked an important milestone in his evolution as an investor.

Let’s look at the prototype of a dream business, our own See’s Candy. The boxed-chocolates industry in which it operates is unexciting: Per-capita consumption in the U.S. is extremely low and doesn’t grow.

A few things jump out:

Business economics are excellent, as evidenced by the high and rising ROIC

Very modest volume growth, barely above U.S. population growth

Attractive pricing in excess of inflation

Overall growth of high single-digits is relatively modest, but the key is that a) it has been sustained for decades and b) it required very little additional capital

This means we have had to reinvest only $32 million since 1972 to handle the modest physical growth – and somewhat immodest financial growth – of the business. In the meantime pre-tax earnings have totaled $1.35 billion. All of that, except for the $32 million, has been sent to Berkshire.

The value of a business growing at X% and able to distribute all of its profits to the company’s owners is much higher than that of a business growing at the same rate but requiring a lot of incremental capital to support that growth

So what did Warren Buffett’s returns look like on his See’s Candies investment? And what would they have been had he paid a higher price?

Buying a “boring” business with low volume growth has netted Buffett a ~ 20% Internal Rate of Return (IRR)!

But only because he paid a very low price. Had he paid up for the business given its quality, his returns would have been far lower

For context, the U.S. stock market had produced annualized returns over this period of around 12%

During my investment career of the last quarter century, high-quality consumer goods companies with high single-digits growth have tended to trade at a Price-to-Earnings (P/E) ratio of over 20x, and frequently above 25x. The returns from such an investment would be very different than what Buffett was able to obtain with his purchase of See’s Candies.

And yet, many investors insist on following Buffett’s public “great business at a fair price” quote and pay up for good businesses. Even though that’s not what he actually does! They then proceed to hold on to these investments for a very long time, again copying Buffett’s quote about his “favorite holding period being forever.”

Guess what? Buying a good but moderately growing business at a high price relative to its profits and holding it forever is very like to produce… market-like returns! Do you really think it can be consistently otherwise in the most efficiently priced capital market in the world?

Let me end with a quick story. When I was a young analyst I went to a well-known value investing conference. On stage, one of the keynote speakers pitched us on the merits of Nestle as an investment. He described many of the company’s strengths but said next to nothing about the price of the stock.

I came up to him after his presentation and asked him at what price he would sell the company. I told him I understood his views on the merits of the brand, the reinvestment opportunities and the management, but shouldn’t there be a price at which that is all discounted?

His answer? Basically “never”!

Not wanting to get into an argument, I held my tongue and didn’t retort that if you act irrespective of price then you aren’t really following a value investing approach.

Nestle is a great company with many strengths. How have the returns of the stock been over the last decade? About 9% per year, or somewhat below the rate of return of the market over that period. Certainly a far cry from Buffett’s 20% IRR on his purchase of See’s Candies. Seems like the price of the stock matters, after all, even for great companies.

If you liked this article, please “like” and share this article. If you are interested in learning more about the investment process at Silver Ring Value Partners, you can request an Owner’s Manual here.

About the author

Gary Mishuris, CFA is the Managing Partner and Chief Investment Officer of Silver Ring Value Partners, an investment firm that seeks to apply its intrinsic value approach to safely compound capital over the long-term. He also teaches the Value Investing Seminar at the F.W. Olin Graduate School of Business.

Note: An earlier version of this article was published on the Behavioral Value Investor website.

Very nice article Gary and thank you for sharing. I think there is one statement in there that might benefit from some qualification.

"However, if that leader translates their greatness into enduring business characteristics, then the competitive advantage can become permanent (e.g. Steve Jobs and Apple)"

The 'if' here should come with a health warning. Jack Welch and GE looked like a great bet at the time of Jack's retirement. He seemed to have GE all set up to weather any storms. He himself was very confident in their success as he retired and, although the market was still suffering the .com slide, the general consensus was that GE would continue to be a good long-term investment. As it turns out, the moats were ephemeral and the succession plan was a disaster.

Even with the benefit of a seat at the boardroom table, reliably predicting how a business will fare following the replacement of a charismatic and strong leader seems doomed to failure.

Iger and Walt Disney Company has a similar ring to it, though we're on a new chapter there.

Great piece. Thanks for putting it out there for us!