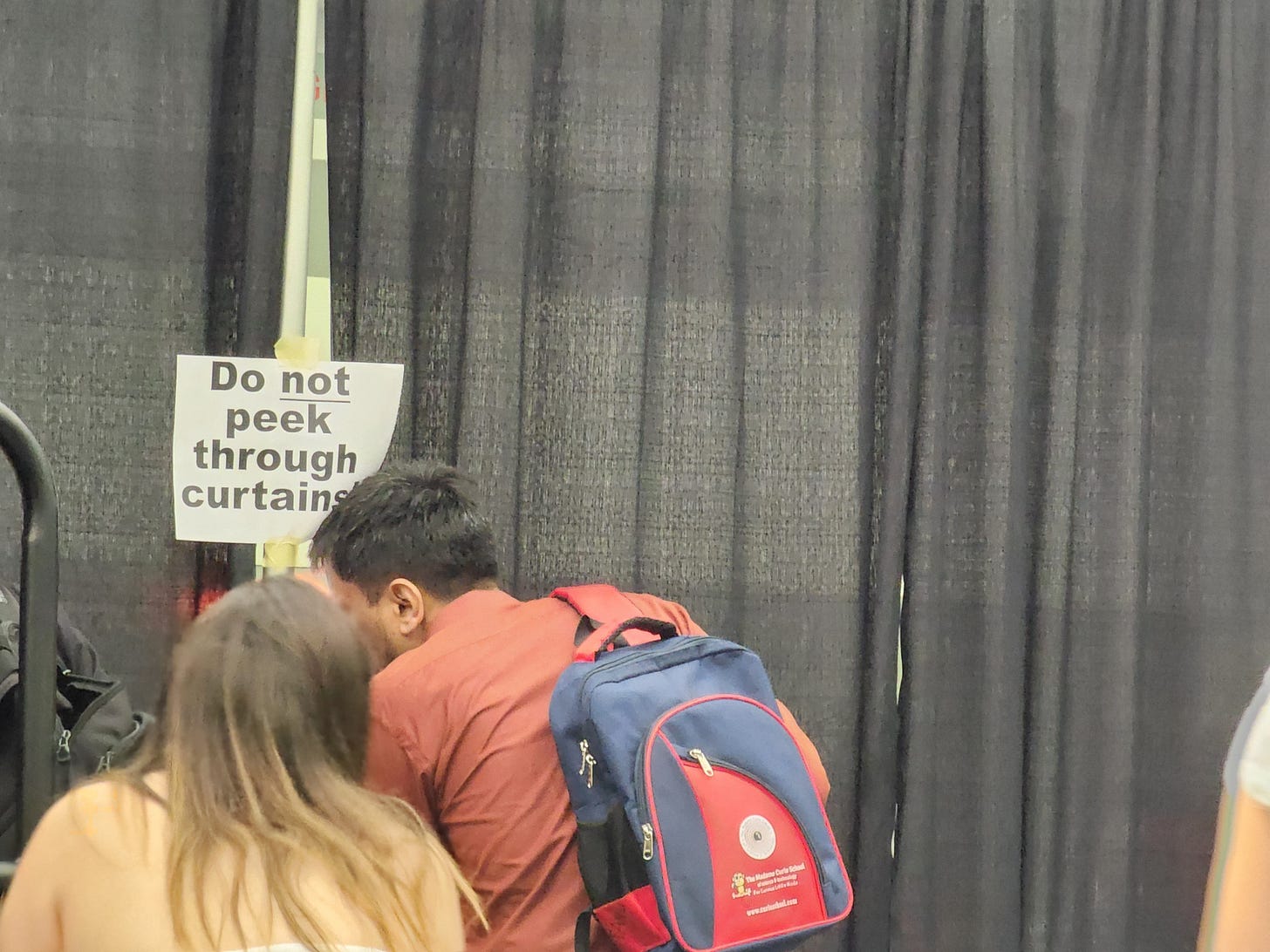

“Do *NOT* Peek Through Curtains”

My son's adventures at the National Elementary School Chess Championship

The tournament director was a no-nonsense army vet. As hundreds of parents sat hushed in the playing hall, he glared at us, and issued a stern warning: “If you peek through the curtains during the tournament, we will spray you with water, like they do when training kittens.”

Well, he elaborated, he wouldn’t actually spray us. However, it would be disruptive to our own sons and daughters who would be competing in the National Elementary School Chess Championship in this hall shortly, and he hoped that we could get ourselves to behave.

My son, Jacob, is in kindergarten, and this was his first national tournament. He loves playing chess, and has been playing since he was 4. When he turned 6, we made a deal. He would do what I told him to as far as chess training for one year, and in exchange I would travel with him to the nationals and he could both play in the biggest tournaments for his age group and also have fun in the places that we would visit. Then, when he turns 7, he can reassess if he wants to keep going and continue to play chess competitively.

The National Elementary School Chess Championship in Baltimore was our first trip. He had played in a few local events around Boston, but nothing like this. He was excited, and so was I.

Being a student of the human mind, I had taken the coaching challenge with eager anticipation, but also with a little bit of apprehension. I have seen all kinds of parental coaching malpractice, both in my days in the last century playing as a kid, and as a parent at the tournaments that Jacob and I have attended.

I remember a father berating his 9-year old son in between rounds at one of this year’s local tournaments. With his son close to tears, the father replayed his game in front of his son and kept pointing out how his opponent didn’t make a single good move, and that it was all his son’s fault for losing. Ouch.

The U.S. Chess Federation publishes “Top 100” lists for chess ratings in each age group. If you look at the old lists, say for 7 year-olds from three years ago, many of them are not on this year’s top 10-year olds list. There are many possibilities for the attrition, but I suspect it has to do with burnout and poor coaching by the parents.

Eager to have their kid improve, parents likely put too much pressure on their young player. They make them do too much hard work in too short a period of time. These helicopter parents think they are giving their child tough love and helping them get better.

In the short-term, they are. However, in the long-term some of them are killing their kids’ intrinsic motivation to keep learning the game and progressing. Hence the high attrition rate of promising young players never making it to their full potential.

Without a doubt, hard work is required to be good at chess. Even Bobby Fischer, the great U.S. chess prodigy, worked incredibly hard to supplement his natural talent. Same is true of every great competitor in any field. The challenge then is how to balance encouraging the hard work to drive progress with nurturing intrinsic motivation and love of the game.

In short, to get a kid to excel long-term, they need to love the game and want to excel themselves for their own reasons, not just because of some external reward.

My approach with Jacob was to focus on the process and on things that he could control. That’s how I approach my investing, and that is what I believe is healthy for long-term improvement.

For example, he can’t control if his opponent finds a brilliant move and wins. However, he can control how much time he takes thinking about the moves, the effort he puts in to practicing, and so on. Over time, quality inputs should lead to quality results.

In the same vein, I try to not to focus on wins or losses, but how well did Jacob play. I am also keenly aware that he is just 6, so sometimes kindness and compassion are more important than clinically precise feedback on what he could have done better. We are all human.

After I helped Jacob find his first round game, I settled in to the chair in the waiting area behind the curtains with hundreds of other parents. The majority of the parents were well behaved and followed the rules. However, overall good behavior lasted only a few minutes.

Thereafter, a few parents started to creep up to the curtains. That encouraged a few other parents to approach the curtains as well. Whether in investing or in daily life, humans like to follow the herd.

Next, some parents positioned themselves next to the cracks in the curtains. Alas, that was not enough. Finally, some bold parent or two decided to break the taboo and peek through the curtains since clearly the rules didn’t apply to them.

It was amusing to watch as the tournament director had to periodically appear and beat back the misbehaving parents from disrupting the players. It would work for about five minutes. It was perfectly rational for the parents to listen to the director. It was even better for their own kids.

Unfortunately, every few minutes the peeking would resume. So much for the rational-actor theory. Overall, the kids were far better behaved than the parents.

Jacob won his first three rounds easily. His preparation paid off.

However, I was getting a bit concerned. At the Nationals, each player has 90 minutes per game to make all of their moves. That is much longer than in local tournaments. It’s also not an easy feat for a 6 or 7 year old kid to use that much time to think per game.

As I waited for Jacob to come out, I heard many versions of some child running out 3 minutes after the start of the game, crying, saying “Mommy I got checkmated in 3 moves!”

I tried to prepare Jacob for this by focusing with him on how important it was to use a lot of time to come up with good moves. I even used a local tournament to practice, telling him that the only thing I wanted him to focus on was on using at least two thirds of his allotted time in each game. He was able to do that, but I wasn’t sure how it would translate into the much longer games at the Nationals.

At the end of the second day, I was getting concerned. Jacob was only using 15-20 minutes out of his 90 minutes. As we walked back to our hotel, I stressed to him again how important it was to use the time. Moving too fast was the same as letting his opponent have an extra piece, I explained. That didn’t seem to get through.

Heading in to the third and final day, Jacob had won 4 out of 5 games. If he were to win the last two, he could possibly get one of the top spots in his section. I didn’t want to focus on outcomes though. Instead, I decided to try again to impress on him the importance of taking his time.

“Jacob, inside each of us there is a chess monster. The bigger the chess monster, the stronger the player. Follow me so far?” He said that he did.

“Ok, great. So you know how you like me to blow up balloons for you?” Jacob made a noncommittal noise of acknowledgement.

“So if I only use a few breaths, will it be a big balloon or a small balloon?”

“Little.”

“Right. So if you want me blow you up a big balloon, I need to use many breaths. That takes a lot of time, right?”

“Right.”

“So the same thing with your chess monster. You need a lot of time to blow it up to make it into a big, strong chess monster. OK?”

“OK.”

“Your opponents in the last rounds will be tough. These are kids who also won most of their games. You will need your big chess monster to do well. But I love you no matter what happens.”

As I dropped Jacob off at his game, I put my hand on his shoulder, looked him in the eyes and said “Big chess monster, OK?” He nodded.

I settled in to wait. An hour passed. Most of the other parents had left the waiting area with their kids. Another half an hour passed. Now I was one of the few remaining parents left.

With all the extra space, I decided to start walking around the waiting area, both to get some exercise and to relieve the tension.

Finally, at the two hour mark, I saw Jacob’s opponent run out of the playing hall. With a smile on his face, he ran to his father.

Not good, I thought and sighed. Time to focus on rewarding process.

As soon as Jacob came out with a serious face, I told him:

“Great job listening and taking your time. You just earned yourself a sticker.”

Jacob nodded. We started walking towards our stuff. Not able to hold off any longer, I asked him:

“So how did it go?”

“Oh, I won.”

I was surprised. I gave him a pat on the back and changed the topic, not wanting to dwell too much on the outcome.

That was game 6. For game 7, I settled in for the long wait. Jacob and I had talked that the least amount of time he should take is 30 minutes, unless he somehow quickly checkmated his opponent.

I was lost in reading an article on my phone, when another father got my attention less than half an hour into my wait. I hadn’t even been looking up to check for Jacob, since I knew he wouldn’t be out for a while.

I smiled, since the only reason for him to be out so quickly would be a quick win. Composing myself, I rushed over to the waiting area to get him. He saw me and his shoulders slumped.

“I lost.”

I looked at the chess clock in his hand. It showed he only used about 15 minutes of his time. In an instant, many thoughts flashed through my mind. About how he didn’t follow the process. How I was spending time and money taking him to the Nationals and he wasn’t even willing or able to take full advantage of the opportunity. How he short-changed his ability to play his best by rushing through the game.

I gave Jacob a hug, and said:

“Want to go get some ice cream and watch the Celtics game?”

There would be time for learning and improvement later. We are all human.

If you liked this article, please “like” and share this article. If you are interested in learning more about the investment process at Silver Ring Value Partners, you can request an Owner’s Manual here.

About the author

Gary Mishuris, CFA is the Managing Partner and Chief Investment Officer of Silver Ring Value Partners, an investment firm that seeks to apply its intrinsic value approach to safely compound capital over the long-term. He also teaches the Value Investing Seminar at the F.W. Olin Graduate School of Business.

Note: An earlier version of this article was published on the Behavioral Value Investor website.

Great story Gary … you definitely get it. Reminds me of the time I ran a “silent” soccer tournament to prevent parents coaching from the sidelines. Talking was only allowed on the field amongst the players. As you can imagine, the kids loved it (parents hated it).

Warren talks about going to work for Ben Graham and summarized it in 3 words. “I became inspired.” Interesting how that process works and how we go about intrinsically developing motivation & passion for a specific topic. Awesome job as a parent, and love the analogy!